Ethiopia, situated in the "Horn of Africa" in the eastern part of the continent, is home to over 120 million people. The capital Addis Ababa has ubiquitous Chinese-financed infrastructure, from highways and subways to skyscrapers and industrial parks. The city has become a hub for African diplomacy, hosting the headquarters of both the African Union (AU) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). With nine UNESCO World Heritage sites, Ethiopia ties Morocco for the most in Africa. Among these is the historic walled city of Harar Jugol, considered Islam's fourth holiest site. Known as the "Cradle of Humanity," Ethiopia is a treasure trove of human fossils, including the 3.18 million-year-old Australopithecus fossil "Lucy" and 4.4 million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus remains. Ethiopia is Africa's only nation that was never fully colonized, barring a brief Italian occupation from 1936 to 1941. This unique history has preserved distinctive cultural elements such as the Ethiopian calendar (based on the Coptic calendar), a unique time system, the Amharic script (the only indigenous writing system south of the Sahara), and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, followed by about 43% of the population. The Ethiopian ethos of "One should not be influenced by others; one should believe in oneself" has been crucial in maintaining these traditions and cultures. In recent years, Ethiopia has achieved economic growth rates approaching 10%. Agriculture remains the cornerstone of the economy, employing about 60% of the workforce and contributing nearly 40% to the GDP. However, the sector primarily comprises small-scale subsistence farmers, leaving them vulnerable to food crises triggered by natural disasters like droughts and floods. Consequently, achieving stable food production remains a critical challenge for the nation.

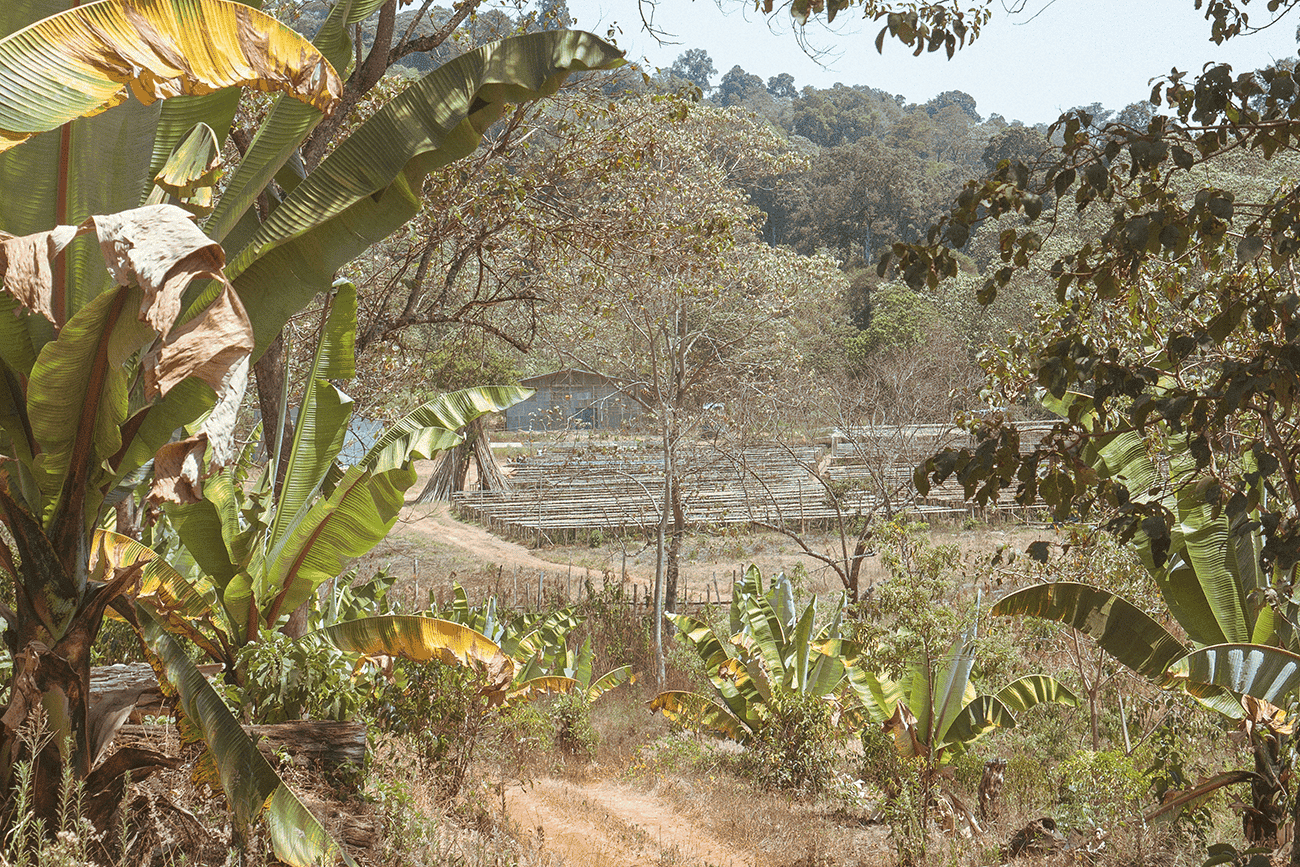

Ethiopia's soil and climate are exceptionally well-suited for coffee production. With little need for pruning or chemical fertilizers, about 90% of the coffee here is grown organically. As you drive through the mountains of Yirgacheffe, you'll find yourself amidst a forest dotted with coffee, banana, and avocado trees. Simple mud-walled homes with corrugated roofs peek out from the foliage. Unlike typical plantations, you rarely find fenced-off farms here. The boundaries between the forest and household gardens are almost non-existent, with coffee trees seamlessly blending into daily life. This unique production environment is rare in the coffee world. The exceptional quality that coffee lovers worldwide covet is naturally present here, requiring minimal human intervention. It almost feels as if we're simply sharing in the bounty that nature provides. Ethiopia's coffee-growing regions can be broadly divided into four types: Forest Coffee (about 10% of production): Wild coffee growing naturally in forests. While it's the most traditional type, its production efficiency is low, leading to a gradual shift toward Semi-Forest and Garden Coffee types. Since 2003, JICA, a Japan-based international aid organization, has been working to conserve this type of coffee. Semi-Forest Coffee (about 35%): This coffee is grown in managed natural forests. The coffee forests are maintained with some cultivation practices such as weed removal and selective clearing for sunlight. Land ownership is established. Garden Coffee (about 50%): Coffee planted by farmers in their backyards or nearby hills, often alongside crops like bananas and avocados. Harvests are typically sold to processing stations or cooperatives for cash. Plantation Coffee (about 5%): Also known as estate coffee, this type of coffee is produced on large-scale private or state-owned farms. They manage the entire process from production to export. These farms can improve efficiency and quality through the planting of specific varieties or the use of technology. Most Ethiopian coffees with a farm name fall into this category, with Gesha Village being a notable example. Ethiopia's Coffee Distribution To understand Ethiopia's coffee distribution, let's examine its history and current situation. Coffee, like wheat and corn, is a commodity (products with uniform value) and is traded in futures markets. Futures trading involves setting future prices in advance, before the physical product is ready. This helps buyers protect against price increases and allows sellers to secure future income. Speculators invest in stocks they believe will increase in value to make a profit. Arabica coffee is traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange, while Robusta is traded on the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange. Arabica coffee futures are divided into three categories: Colombian Milds (washed coffee from Colombia, Kenya, and Tanzania) Other Milds (washed coffee from other producing countries) Brazilian Naturals (natural process coffee from Brazil, Ethiopia, etc.) The international price (C-market price) fluctuates mainly based on supply and demand balance. These significant price swings can destabilize producers' livelihoods. In 1962, the International Coffee Organization (ICO) established the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) to stabilize prices by limiting coffee exports (export quota system). However, due to dissatisfaction from both producing and consuming countries and the US withdrawal from ICO, the export quota system was suspended in 1989. Even after the suspension of the export quota system, coffee consumption has continued to grow yearly, and its popularity as a speculative commodity hasn't diminished. Consequently, international coffee prices remain highly volatile. The production volume and economic conditions in Brazil, the largest producing country, also greatly influence international prices. In 2019, international prices plummeted, reportedly falling below production costs, due to an abundant harvest in Brazil and a weak Brazilian real. Although Ethiopia's production accounts for only about 5% of global coffee output and has little impact on international prices, Ethiopian producers are still susceptible to futures prices. Several initiatives have emerged in Ethiopia to address this situation. In 1999, the Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union was established. The union successfully brought certified coffees (Fair Trade, Organic, and Rainforest Alliance) from Oromia to international markets. Their system returns 70% of gross profits to local Primary Cooperatives. The union dispatches trainers to these cooperatives to teach sustainable production methods. The Oromia Cooperative's efforts gained worldwide attention through the documentary film "Black Gold." In 2008, the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX) was founded as a private company in partnership with the Ethiopian government. ECX handles various commodities, including coffee, sesame, and corn. Before ECX, coffee producers had no means of knowing market prices and lacked negotiating power when selling coffee cherries, with quality not factored into pricing. ECX addressed these issues. ECX shared market price information with producers through its website, electronic displays at trading floors, SMS, and toll-free phone calls. It classified coffee into nine major production regions and graded them (e.g., Yirgacheffe G1, Sidamo G2). All coffee, except from cooperatives and plantations (private or state-owned farms), had to be certified and graded by ECX and traded through auctions. Notably, ECX was designed for commodity coffee, which accounted for about 96% of production at the time, rather than specialty coffee. Under ECX, Ethiopian coffee could only be identified by regional name and grade, making traceability difficult for importers who had previously engaged in direct trade with specific processing stations. This change undermined existing relationships and investments in processing stations. In 2009, ECX held discussions with SCAA (now SCA) and introduced quality evaluations by Q Graders, moving closer to the specialty coffee industry. In 2017, ECX finally elaxed regulations, allowing individuals and small businesses to obtain export licenses, making direct trade possible. This deregulation has improved the traceability of Ethiopian coffee. Since 2017, suppliers and producers have begun functioning as exporters. 2017 can be considered the first year of direct trade in Ethiopia. In 2020, Ethiopia held its first Cup of Excellence competition, further emphasizing this shift. Moplaco and Wete Ambela Coffee serve as our curators for Ethiopian coffee. Moplaco is a long-established coffee company that has experienced everything from the era of international price fluctuations to the birth of specialty coffee and beyond. Wete Ambela Coffee, founded in 2018, is a startup aiming to pioneer a new era. Understanding the backgrounds of these two companies is equivalent to overviewing the history of Ethiopian coffee. We hope you will appreciate not only the coffee but also the historical turning points behind it.

Warehoused

Nardos Coffee 2021/22

Producer/Curator:

Biniyam Kassa

In a traditional coffee producing country, major changes are afoot. In Ethiopia, an increasing number of young coffee producers are gaining a morale boost, with the easing of ECX regulation and the start of the Cup of Excellence. Among them is Biniyam Aklilu. We got to know Biniyam through the introduction…Read More

1,560roasters are interested

270roasters purchased

Sample Request :

Start

End

Pre-oder :

Start

End

Warehoused

Moplaco 2021/22

Producer/Curator:

Heleanna Georgalis

Heleanna Georgalis, the director of Moplaco, was the first curator for TYPICA. When I visited Ethiopia the year before last for the first time, Heleanna was the only person that I could get an appointment with. She accepted us even though we had no experience in the coffee importing business. She took care of…Read More

1,793roasters are interested

149roasters purchased

Sample Request :

Start

End

Pre-oder :

Start

End

Warehoused

Wete Ambela Coffee 2021/22

Producer/Curator:

Mekuria Mergia and Elias Yifter

We are on our way to the washing station in Guji with Mekuria and Elias in a four-wheel-drive car. The natural environment here is different from that of Yirgachefe. We alternated through gently rising green hills and dusty red dirt off-roads. Houses with colorfully painted walls, people washing clothes in the river, and…Read More

3,816roasters are interested

466roasters purchased

Sample Request :

Start

End

Pre-oder :

Start

End

Price

9.3 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

9.3 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

9 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

9 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

10.6 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

15.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

9.7 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

9.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

13.2 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

10.5 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

14.7 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

14.7 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

15.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.6 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.6 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.6 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

8.6 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

24.3 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

7.5 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

15.4 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-

Price

6.3 USDFOB/kg

Quantity

0/0 bags (60kg)

Samples

Out of Stock

-