HONO roasteria has a motto to roast coffee that doesn’t tire you out. In addition to selling roasted beans to wholesale clients like cafes and restaurants, the roastery also sells its products to general consumers on an e-commerce website and at pop-up events.

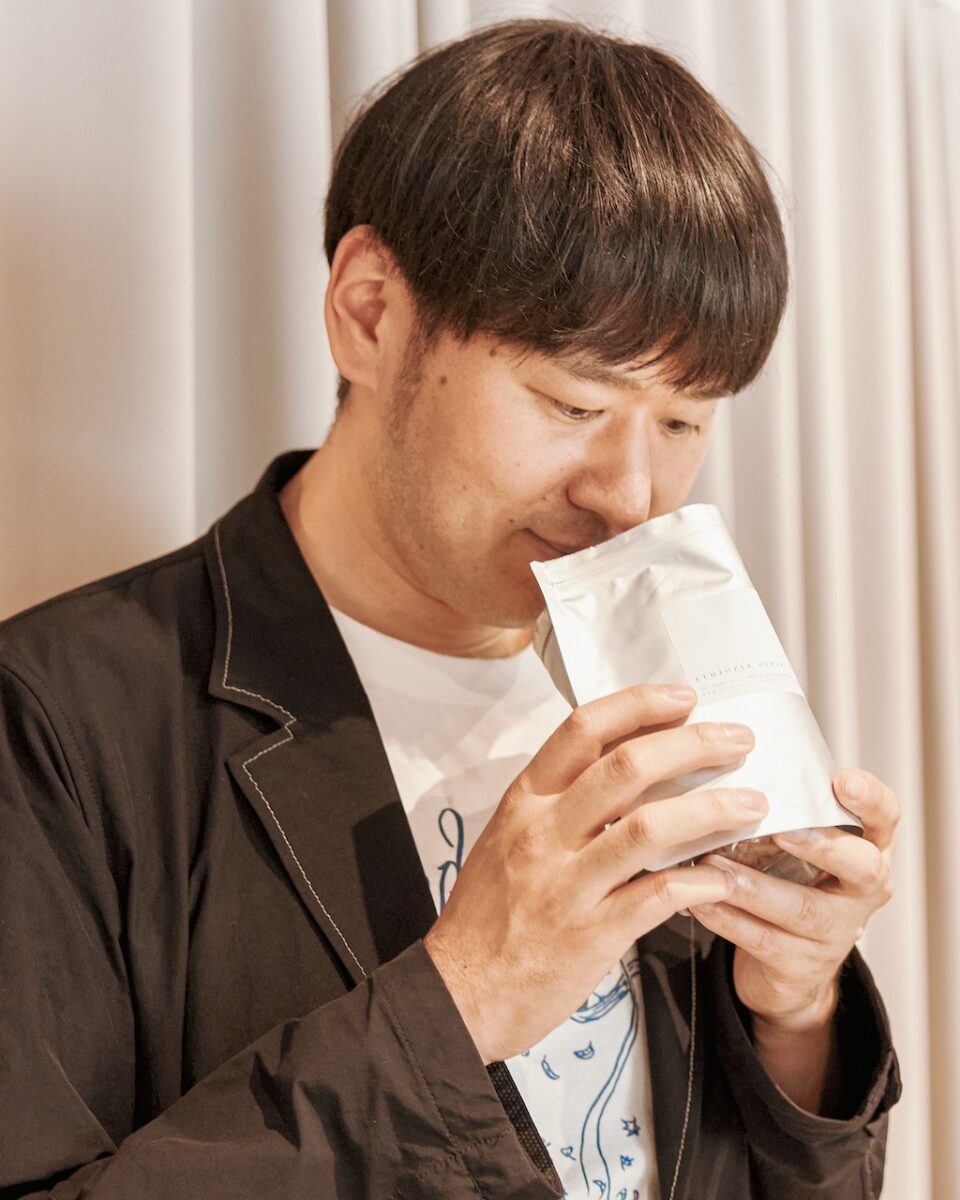

Tatsuya Murai founded HONO in 2010. A former violin craftsperson turned roaster, Murai was once single-mindedly focused on becoming a violin maker. How did he end up leaving the world of music instruments and making a foray into the world of coffee? We spoke to Murai to find out what it is about coffee that has continued to capture his heart.

Deliciousness where static and dynamic coexist

Deliciousness is an extremely complex and vague concept. According to the Specialty Coffee Association’s criteria, coffee has to be rare and clearly possess distinctive flavors to earn high cupping scores. But scores don’t always translate into deliciousness, much as coffee brewed by competition winners or famous roasters is not guaranteed to be tasty. Coffee’s deliciousness, after all, varies depending on personal preferences, its appearance, the environment where you drink it and your mood when you drink it. It goes without saying that different people pursue different types of deliciousness.

“Deliciousness created by coffee roasting has static and dynamic values. They are both important,” Murai says. “What I find appealing about coffee are freshly roasted beans’ fragrance, distinctive flavors unique to different origins as well as brewing techniques to find a narrow sweet spot. Stories and information behind a cup of coffee can sometimes enhance my sensibilities. What I mean by static values is the comfort you get when the coffee you are drinking here and now is simply delicious.

Dynamic values, meanwhile, are lasting deliciousness. It’s better if everyone can easily bring out the intrinsic deliciousness of coffee beans. Likewise, it’s better if coffee stays delicious and provides people happy moments for three months, rather than losing its deliciousness in two weeks. First and foremost, coffee obviously has to be delicious. But besides that, its medicinal effects also have to be designed, too.

These are the two values I keep in mind when roasting coffee because coffee with both static and dynamic values can open up a world beyond the imagination of even its producers.”

Momentary deliciousness and lasting deliciousness. These two kinds of deliciousness are sometimes seen as contradictory values — values that can’t coexist. Some see them as a trade-off where one can’t be achieved without sacrificing the other. But Murai pursues a world that emerges when these two values melt into one.

“For instance, good and evil are often seen as opposites. But they are actually not. Seeing them as opposites is merely one perspective, or an illusion for that matter.”

Murai tries to keep himself neutral to avoid tilting toward one particular perspective. He believes humans become desensitized if they get the same stimulus day after day. To stay away from this tendency, he makes it a rule to drink no more than two coffees a day, unless there are strong reasons, and to block out a week where he pays no attention to the quality of acidity.

“When you run a coffee shop, it’s not unusual to drink around 5 cups of coffee a day. Your body begins to adapt to the habit, and before you realize, your measurements of taste will change. I’ve seen a few people who left this industry after falling ill from drinking excessive amounts of heavy coffee. Coffee has strong medicinal effects. That’s why I want to handle it carefully. This idea is driving my pursuit of coffee that doesn’t tire you out.”

Murai, who makes it a motto to stay open to all options, lives by the principle of positive self-denial. It means that he deliberately rejects things he thinks are good or he believes in.

“Some roasters believe there is a single right answer to roasting methods and theories. But that is just the right answer for that particular individual. I have to find the right answer for myself. Coffee’s tastes are influenced by various factors like environmental circumstances and beans’ conditions. It is vital to fine-tune them in each step. If you keep reaching out for an answer that way, it will come to you.

What is considered the best possible method now may happen to be a work of perfection that can’t be improved upon. But if I get a new perspective or approach, I might be able to create something new. Some people may be reluctant to do so. But as someone coming from the world of musical instruments, no other pursuit can be as casual as coffee.

It takes a tremendous amount of time to put together a single violin. In my case, I was making violins while doing repair work, too. So it would be good enough if I could make two violins a year. I assume everyone can imagine how difficult it is to put new ideas into practice, learn something and keep making improvements. In that regard, coffee is very alluring because you can roast one batch in 15 to 20 minutes, which allows you to try out different ideas repeatedly.”

Path found when working as violin craftsperson

Quite a few people in the coffee industry have come from other sectors. Murai, a violin craftsperson turned roaster, is one of them. But for him, one profession is an extension of the other. His current values of harmonization between the static and dynamic originate from when he was a violin craftsperson.

Murai was in his teens when music became an integral part of his daily life. He wasn’t discriminatory when it came to genres, and one of the things he most intently listened to was classical music on CDs. But classical music is unplugged, meaning that it is played by instruments without electricity. To have more real experience, Murai started going to live concerts to listen to unfiltered sounds.

“I had a really great experience at a concert at Kioi Hall in Tokyo. It featured French pianist Pascal Roge, who was 44 at the time and in the prime of his career, and 2 up-and-coming musicians, violinist Mie Kobayashi and cellist Yoko Hasegawa. The trio played a score by Ernest Chausson. Communication between the three was wonderful, from Roge’s generous lead to how the three paid attention to each other. Each of them did a great job of expressing their phrases and key sequences to the audience. They even used breathing patterns and eye contact to bring into real life music playing inside them. It was a magical time packed with various levels of brightness.”

Ever since that day, when the three musicians looked like rock stars to Murai, he had an irresistible desire to play a stringed instrument himself. Having settled on the cello, Murai managed to buy his own piece and pay for lessons by eating into what little savings he had, trying to improve his performance skills. But as he started to visit instrument stores and workshops for maintenance, the object of his interest began to shift toward musical instruments themselves.

“I tested various instruments. I found it interesting how different instruments produce different sounds. As I got to know craftspeople at stringed instruments trade shows and later visited their workshops, I began to feel a desire to become a stringed instrument craftsperson. Stringed instruments are hollowed-out wooden boxes with 4 strings. But I wondered how such simple objects could produce sounds so rich. My curiosity took me deeper and deeper into the allure of stringed instruments.”

After a period of apprenticeship, Murai started to make instruments at a workshop of a stringed instrument importer. He received a stream of creative stimulation as he saw many violins made by various craftspeople, sometimes as part of the job and at other times in his personal life. And Murai noticed something.

“Violins have an interesting contradiction that every instrument craftsperson runs into. Some violins are structured well but not excellent as a musical instrument. On the other hand, some, like Giuseppe Guarneri, are good as musical instruments but not structured well.

In my personal view, musical instruments have two criteria of appeal. One is how well they are structured, or static values in terms of designs and shapes. The other is the ability to produce sounds, or dynamic values in terms of the breadth of its sounds during performance.

These two criteria are independent of each other. So it’s necessary to cultivate the talent and skills for each. To enhance violins’ static values, you need to have a fine sense of craft art. To pursue their dynamic values, you need to have a fine sense of architecture.

Violins have the longest longevity of all instruments. The violin family (the violin, the viola and the cello, in descending order of range) made by Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) about 350 years ago are considered the cream of the crop at the moment.

Stradivar is a maestro liutaio, the world’s most famous stringed instrument craftsperson hailing from Italy’s ancient capital of Cremona. He also made guitars and harps, but other stringed instruments are not as durable as the violin family.

The secret to the violin family’s longevity lies in the fact that energy inside the instruments is stable. The top board and the back board, which amplify sounds and create reverberations, are shaved out in an arch shape without any straight line or flat surface. These instruments also use timbers with different levels of resilience for different parts. The more I learned about their structure, the more I was surprised. I realized that they are small pieces of architecture, completed with no excess.

The most memorable instrument I have ever seen is a Stradivari cello owned by Danjuro Ishizaka, a German cellist of Japanese descent. Once, he showed it to me backstage in his dressing room. I was overwhelmed by the godly beautiful work of Stradivari. A Felix Mendelssohn cello sonata Ishizaka played in that recital was amazing, both in terms of performance and range of sounds.

His cello was made in 1696. Its intricate and dynamic structure is extraordinary when you think about the circumstances at the time. Stradivari’s excellence lies in the fact that he designed and created something that did not yet exist in his time, and yet produced the great result.

But of all stringed instrument craftspeople, I was most attracted to Ferdinando Garimberti (1894-1982) from Milan. He was born long after Stradivari was gone. His career started after he hit it off with Romeo Antoniazzi, another stringed instrument craftsperson, and found instrument making appealing. Before that, he was working as a blacksmith in his family business and ran an inn with his wife.

Since Garimberti was used to handling tools as a blacksmith, his talent blossomed as an instrument maker as well. He is a key person in the history of instrument-making. He also taught at an instrument-making school, too. Back then, many craftspeople from Milan were making uniquely shaped instruments. But his beautiful, original models were so organic that they give off the energy of life and have a really sexy arch. In addition, the sounds and range of expression are very rich and glamorous. I think he is the archetype of craftspeople who embody both the static and dynamic.

The beauty of Garimberti’s works is that they bring his vision into sharp relief. It’s really cool that his instruments are unique yet exceptionally great skill-wise. It almost feels like they are bringing magic to life.”

Pursuing infinite possibilities

Murai had an unexpected encounter in 2007 when he was walking a career path as an instrument craftsperson without a cloud of doubt. It took place at an espresso bar in Tokyo’s Akabane-bashi district. The bar was like a version of Espresso Vivace, a Seattle-based cafe owned by David Shomer, a world-famous espresso evangelist.

“I bought beans there. I still remember to this day how delicious it was when I brewed them at home. The staff didn’t necessarily explain to me in words who produced the coffee, in what method it was processed or what background it had. But a view of a coffee farm I’d never visited unfolded in my mind. The taste of the coffee itself had the power to evoke the roots of the beans.”

The evocative, emotion-arousing experience compelled Murai to visit the store again. To experience that same taste, he bought coffees of the same origin and variety. But every time he did, his expectations were unfulfilled. Why, he wondered, they tasted different, despite being the same beans? Curious, Murai asked staff members at the shop.

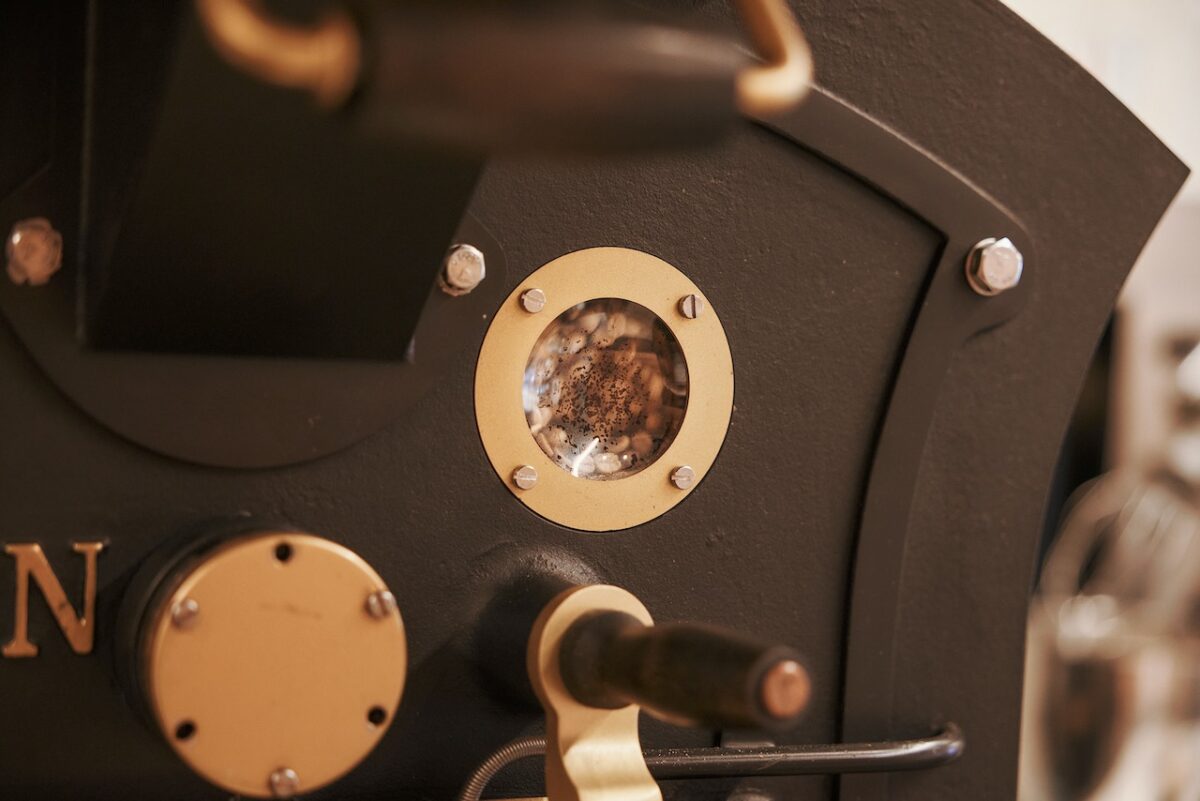

“They told me, ‘The beans were roasted by someone in training without data being recorded. They were pulled out of the roaster without much control on temperature or time. So it is impossible to replicate the same roasting. You could say it’s a batch that’s lost forever.’ The staff, too, thought those beans were very delicious. But they were frustrated about not being able to replicate them. Back then, machines were not as stable as now and it was hard to control temperature.”

Beans he bought at the store were sometimes not as tasty as he expected, but at other times far more delicious than he expected. Wandering into a world full of mysteries, his heart constantly yearning for that single cup of coffee, Murai felt infinite possibilities of coffee.

How beautiful it would be, he thought, if there was a coffee shop that could turn out that coffee 100 times out of 100 roasts. With that dream scenario in mind, he started to absorb himself in roasting and fiddling with machines in his spare time while working another job.

“I modified roasters with a 100-gram capacity and espresso machines. I also created software that records roasting profiles with the help of tech-savvy people. I launched a website called ‘latteArtChronicle’ and uploaded images of my ‘play.’ I didn’t have the slightest intention of starting my own coffee shop. But I think I roasted 2,000 to 3,000 batches in total.”

Murai founded HONO in 2010 after being involved in coffee as a hobby or side job for a few years. That was because he followed his inner voice, saying that he didn’t want to stand by watching the coffee scene gaining steam around him. Ever since, he has pursued coffee’s infinite possibilities through roasting for more than a decade.

“Coffee farmers make an effort to grow their coffee to earn better recognition. After it is harvested, it is depulped, dried and packed into bags before being transported on aircraft or ships to consuming countries. This process has a lot of room for improvement. But it also means that there is a lot of room for growth. Now that consuming countries have been actively working to help make delicious coffees, it is exciting to think that this happiness spiral will help realize a future where we get to drink higher-quality coffee.

It’s a long road from the seed to the cup. And many people are involved in coffee. We roasters can only be involved in about 10% of the process of making coffee’s taste. Part of me wants to roast coffee that I grow myself. But if I choose to do so, I’d have to ask a lot of people to contribute an enormous amount of knowledge and skills.

Whereas the whole process of violin-making can be completed on a desk, you can’t possibly be involved in coffee-making from A to Z, and that’s the beauty of it. It only takes one small mistake to change the taste of coffee drastically. But that’s precisely why it can work magic on those who drink it. Nowhere else in the world could you find a beautiful magic of such a grand scale.”

Having left the world of instrument-making, and now steeped in the world of coffee, Murai’s rock star continues to be Garimberti. His trial and error, where he never becomes satisfied with the status quo and opens himself to anything to further evolve, is bringing him closer to his idol.

“I felt a strong affinity toward Garimberti when I found out that he also played the cello like I did. He turned from a blacksmith to a stringed instrument craftsperson. He created a magical time through his work where the static and dynamic coexisted. As for me, who turned from a stringed instrument craftsperson to a roaster, I am making a coffee named “MAGICO,” or a wizard, to bring a similar experience to someone else.

Originally written in Japanese by Tatsuya Nakamichi

Photos by Kenichi Aikawa, PASSAGE COFFEE, ambos

MY FAVORITE COFFEE

I like the first coffee I drink in the morning. It’s better to ingest something good when my senses are sharper. Also, deliciousness is all the more comforting when I drink coffee when I want to. For the same reason, I have huge respect for coffee shops that are open from early in the morning.