Journal

#3

The tumultuous politics and undaunted tenacious spirit of Nicaragua

Most coffee producing countries are relatively poor. Many are strangers to democracy, with an unstable political climate that is an easy target for dictatorial rule. Nicaragua is a textbook example. Civil war and revolution successfully removed the right-wing dictatorship, only to have a left-wing dictator step in and take power. My first visit to the country was in 1984, right in the middle of the civil war.

Battle at the border

Civil war, which pits citizens of the same country against one another, is a tragic thing to witness. In 1984, Nicaragua was ruled by the left-wing revolutionary government. Soldiers of the displaced right-wing dictatorship had fled north across the border to Honduras, and were leading guerilla attacks across the border. The battle was being fought in the region around the border.

This war zone is also the main coffee producing area for Nicaragua. I visited the border town of Ocotal in the Nueva Segovia Department, an important hub for coffee production. The town is 20 km from the border of Honduras, and a 230 km drive north from the capital along the Pan American Highway.

The town had suffered guerilla attacks as recent as a month before my visit. I stood at the crossroads in the center of the city and took in my surroundings. The whitewashed walls of the buildings were pierced with hundreds of bullet holes. The deeper the hole, the closer the shooter to the building. Other facilities had been burned down, including the coffee distribution center and the town’s broadcasting station. Sandbags were piled high across the roads preventing traffic going in or out. Outside the city sat 16 tanks all with their guns pointing north. “We’re surrounded by guerilla forces,” the manager of Hotel Frontera told me with a defeated look. “We live in constant danger.”

I took a trip to the frontline. From a hill near the border, government troops laid down a constant barrage of gunfire. Standing next to a cannon with a barrel at least four meters long, I spotted a young boy shouldering an automatic rifle. Hector Gonzales, a school boy of 12 who had volunteered to join the fighting. When I asked him why, he answered, “Because I want to go to school.” His reply left me with more questions than answers.

“If my country is fighting, I can’t focus on my studies,” Hector explained. “The more soldiers join, the quicker we can win the war and the quicker it’ll be over. Then I can go back to school!” Hector spends half the year fighting as a soldier, and half the year studying in school. “When I grow up, I want to be a marine biologist,” he added, eyes sparkling with a powerful determination.

In an environment where life is uncertain from one day to the next, his chances of making it to adulthood were slim. Which made his confidence even more exceptional. Here he was fighting a war, yet dreaming of becoming a researcher. The cruel reality he lived was not weakening his will, but requiring him to assert it more than ever. It’s this quality, this assertive character, that I admire most in the people of Nicaragua.

Carrying a gun to harvest coffee

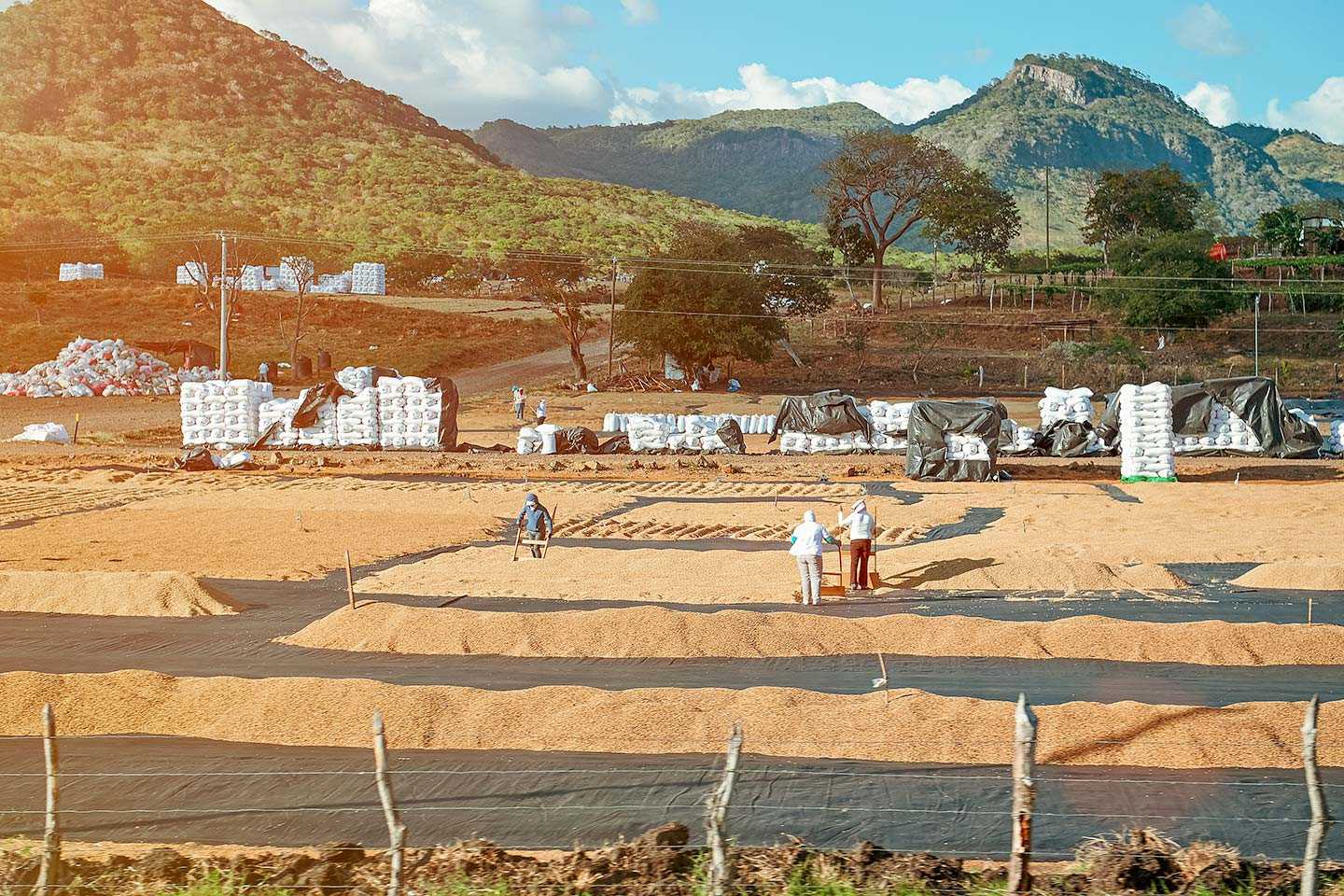

I visited the mountain region of Matagalpa in the middle of harvest season. 180 villagers were harvesting cherries from the coffee trees that covered every inch of the mountain slopes, stretching high to pick and bending low to drop them in the baskets. The men shouldered automatic weapons. When the basket was full it was taken down the hill and the cherries spread out on the drying mat in the garden.

There, separating the ripe cherries from the green were two young children: 11 year old Bernarda and her younger brother, ten year old Fabio. They’d been coming here to work the two month winter holiday every January to March since they entered school.

The two young siblings start work at 6 am and finish at 4 pm. For ten hours, Bernarda and Fabio sit under the hot sun, performing the same monotonous task. Bernardo was already an old-hand with four years experience under her belt. Fabio wears a governmental soldier’s hat, a hand me down from his father. I noticed he had a large rip in the knee of his brown trousers, and other sections were ready to split with wear. Working on the same farm, their parents don’t have time to repair the children’s clothes.

“When I grow up, I want to be a doctor,” Bernarda told me. “It’s the best way to help people. When people in the village get sick, I’ll make them better.” Bernarda picked up a coffee bean and held it up between two fingers. “I bet they all look the same to you, but they’re not. They all have different personalities.” Bernarda may have handled plenty of beans, but she has never had even a drop of coffee.

The harvested beans are processed at Beneficio San Carlos at the foot of the mountain. Once the beans have been dried and processed, they’re bagged and shipped out to Europe and elsewhere. All the workmen at the mill were dressed in the same blue clothes and nobody was talking. I tried to strike up a conversation. I was met with silence and an uncomfortable smile. These workers were in fact prisoners – soldiers of the regime in power before the revolution, sentenced to 30 years in prison. The blue clothes are their prisoner uniforms. They are brought to the mill every morning, work all day and then return to their cells in the evening. Some of the prisoners have already served seven years.

I counted 250 workers at the mill, all making quality coffee for export. “The war forced us into the mountains last year, so we harvested late. But this year looks like we’ve got a good quality bean,” Marta in accounts told me. The progress of war has a direct effect on the progress of their business.

In Matagalpa City, there was an office recruiting laborers for harvest season. Posters shouted, “Join the fight for coffee! Women Producer Brigade!” Another called, “Women to the trenches! Fight for peace and revolution!” Female soldiers are a common sight in Nicaragua, a country of strong, independent women. I learned later that they successfully recruited 252 people to work on the coffee farm for one month.

The Sandinista Revolution

The Sandinista revolution of 1979 brought an end to the long-ruling military dictatorship of the Somoza dynasty. The Sandinista were the Sandinista National Liberation Front, a leftist guerilla army who fought for equality and a fair distribution of wealth. Their name was inspired by Augusto César Sandino, the assassinated leader of Nicaragua’s nationalist rebellion.

In 1979, the Cold War was still ongoing. After the revolutionary government took power in Nicaragua, the anti-left-wing administration of US President Reagan recruited counterrevolutionaries and established bases in the border areas of the neighboring Honduras, arming and training them to launch guerilla attacks across the border. These activities were funded by the US. In other words, this was a war created by the US.

Nicaraguans turned their anger at the manipulation of the Western superpower into staunch support for left-wing politics. The leftists, however, were not all military men. The majority were cultural and learned figures. The Vice-President was a writer, and there were several poets in the cabinet.

Religion also had a place in the cabinet. There were not one but four catholic priests. The catholic religion tends toward conservatism. However, during this period, the progressive liberation theology was gaining popularity in Latin America. This ideology sought to bring about social change for the poor and oppressed through the involvement of the faith in political and civic matters.

One of these priests was Ernesto Cardenal, the Minister for Culture. He created a farming community in the Solentiname Islands, an archipelago in the south of Lake Nicaragua, and encouraged the locals to express themselves through art. The locals painted in oil, producing images of the landscapes around them, capturing each leaf in exquisite detail in the art movement that became known as primitivist art. There, painted in vivid prime colors, were the daily lives of the locals.

Among these pieces is the work entitled “El Café en su Florecimiento (Flowers blooming in a coffee field)”. Lush green dominates the painting. In the foreground stand coffee trees spotted with white flowers and red cherries, and in the background a person on a sailing boat, a rabbit hiding in the shadows of the forest and a flock of colorful butterflies alighting on a field of flowers.

Mexican art critic, Ida Rodríguez Prampolini, once said, “In their pursuit for truth and in their battle to own their reality, the Nicaraguan warrior and the Solentiname painter are one in the same.” In Central America, art is also a battle.

In the slums of the capital Managua, I met Oneida, a girl of around 14 or 15. “Everyone is the same since the revolution, we’re all equal now,,” she told me. “I’m learning how to play the violin. But if there wasn’t a revolution, I wouldn’t be going to school, never mind learning an instrument.” This was a period when people suffered from both poverty and war, yet they still sought art and culture, and found hope to live. The fact that they created an art movement while also fighting a civil war is testament to the creative and ambitious spirit of the people of Nicaragua.

Collapse of the Revolution

The civil war ended in 1990. A peace agreement was formed and after the elections were held, the Sandinistas were defeated and replaced by a centrist government. After decades of fighting, the citizens of Nicaragua no longer wanted left or right, but a neutral political agenda. However, the post-war recovery did not go as planned. Some of the new cabinet ministers appropriated mansions of the rich who had fled the country, and used their political power to increase their own wealth. As the situation got worse, political rivalries increased and the leftist Sandinistas once again rose to power.

The victor who eliminated his political rivals to take power was the left-wing fundamentalist, President Daniel José Ortega Saavedra. Ortega abolished the rule forbidding presidential re-election, named his wife vice-president and established his dictatorship. Those who could not agree with his politics left the Sandinista.

In 2018, demonstrators gathered in several cities to protest against the government. The police used force to suppress the protests resulting in the death of more than 300 citizens. The protests led to the arrest and incarceration of leaders of the opposition party, and the country has become a society ruled by oppression. The politics have changed from right-wing to left-wing, but Nicaragua is still under the power of a dictator – one whom a local journalist colleague told me gets more like Stalin every day.

International firms have left the country, and the already depleted tourism industry is almost non-existent. In 2018, economic growth was at -3%. The poor living conditions forced more than 100,000 citizens to flee the country as refugees. Many others left to find employment.

Then, in 2020, the pandemic hit. While other countries in the region reported cases in the millions, Nicaragua was reporting in the tens of thousands, Hard to believe that this is the truth. More than likely, the real truth is hidden deep. Ortega cannot keep his hold on power for much longer.

As for those Nicaraguans who have tried to escape this regime, their outlook is no better. Many of you may recall reports of the then president Trump closing the border on an influx of refugees from Central America. Some of these were Nicaraguans. Even if they successfully make it across the border, they are unlikely to be granted a visa, and chances of making a life for themselves are slim.

Many Nicaraguans choose instead to migrate to the neighboring Costa Rica, which has a welcoming policy for accepting asylum seekers and refugees. People who enter the country are not placed in refugee camps, but given governmental support to settle in the country as independent individuals. After five years, they can then apply for citizenship. Many of the workers on coffee farms in Costa Rica are migrants from Nicaragua. Some are settled as citizens, others are seasonal workers. While Nicaragua’s economy gets steadily worse, this new labor force is helping Costa Rica’s economy to advance.

Hope for Recovery

That’s not to say that the people of Nicaragua have lost hope. After all, these are the people who successfully brought about a revolution. They won’t remain under the power of an oppressive regime forever. In fact, there are already independent economic movements underway.

In Ocotal, the border town I mentioned earlier, lives Julio Peralta, owner of Peralta Coffees. When he visited Japan in October 2022, I had the opportunity to interview him.

Julio is owner of a fourth-generation farm in the border region, a large-scale plantation of 74 hectares. As a child he remembers riding on the back of a truck to help out with the harvest at the farm. During the civil war, he went to the US to study at university. After the war, he came back to his hometown and has been working to revive the coffee industry in the local area.

But it has been an uphill struggle. Volcanic eruptions and major earthquakes, the coffee price crisis meaning that despite a good harvest, he couldn’t get the price he wanted. Then, when he finally saw an upturn in fortune, came the 2018 protests and he could no longer export. Many of his farming colleagues have left the business for good.

“We coffee farmers should stand straight in the face of adversity,” Julio told me. “Climate change, labor shortages, political shifts – there’s always going to be problems. But we Nicaraguans are tenacious by nature, and we’ve got to keep pushing forward.”

Nicaraguan coffee is harder to come by than most. But its assertive character makes it an exceptionally good coffee that is impossible to put down.

Top Photo: Jorge Mejía peralta

Second Full-width Photo: Susan Ruggles