Journal

#7

Gentle-Tasting Coffee from a Violence-Riddled Nation – Colombia's Melancholy

A country that serves as the entryway to the South American continent, Colombia is brimming with fascinating attractions beyond its world-famous coffee. It's a land of gold, emeralds, narcotics, and exotic orchids. The common trait amongst these is their uncanny ability to captivate the human heart, often leading lives astray. Despite Colombian coffee's renowned mildness, the society here has a historical undercurrent of violence. Years of political discord resulted in civil war, and it remains the sole South American nation still grappling with the existence of guerrillas. Add drug cartels to the mix, and you have a chilling portrait akin to the one painted by Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Márquez, a native of Colombia. It begs the question: How did such mild coffee originate here?

The Coffee Kingdom that Arrived Late

The credit for bringing the African coffee tree to Central and South America goes to Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, a French naval officer. He carried saplings nurtured in the botanical gardens of Paris via sailboat to Martinique, a French-governed island in the Caribbean. The journey spanned two months, punctuated by intense storms and pirate attacks. When marooned at sea for over a month due to lack of wind, he selflessly used his limited drinking water for the sapling — a tale that’s nothing short of poetic. Whether it’s completely true or not, the saplings indeed took root on the island, culminating in a successful harvest in 1726.

Coffee trees arrived in Colombia in 1732, six years later. Based on “The Orinoco illustrated and defended,” penned by a Jesuit priest, the first coffee tree was planted in the courtyard of a monastery situated at the river’s confluence. It rapidly proliferated in the 19th century when the priest required his local Catholic followers to plant coffee trees as a form of penance. It suggests that the believers were sinning continuously, one sin leading to another.

However, the quantity was a mere drop in the ocean when compared with next-door Brazil and Costa Rica in Central America, both of which had firmly secured their status as coffee heavyweights. It was only in the 1870s, when consumer buying power in Europe and America strengthened and technology advancements slashed export costs, that Colombia’s coffee production exploded to a globally competitive level. The nation, a latecomer in this arena, adopted a strategy of mimicking Costa Rica’s high-quality coffee production and replicating Brazil’s high-quantity production.

One of Colombia’s major advantages is its vast regions that are conducive to coffee production. The country is situated at the northern tip of the Andes, a mountain range that splits into three distinct ranges within its borders, thus offering numerous high-altitude slopes fit for coffee farming. Here, ideal conditions for coffee cultivation – altitude between 800-1900 meters, temperatures of 17-24 degrees Celsius, and annual rainfall of 1500-2000 millimeters – are plentiful.

In Brazil, the enormity of the land leads to expansive coffee farms and a tendency for not-so-meticulous farming methods. The growth of coffee plants can be irregular, with harvests often comprising a mix of ripe and unripe fruits. In contrast, Colombian coffee trees, sprouting on the steep mountainous inclines, have an almost uniform growth pattern due to the colder conditions. Moreover, farmers here diligently handpick only the ripe berries.

This practice led to Colombian beans outshining Brazilian beans in terms of quality, which didn’t go unnoticed by consumers. Production saw a sharp uptick, and by the 1910s, Colombia rose to become the second largest coffee producer globally, trailing only Brazil. During this period, there was a fervor to populate the entire country with coffee trees.

Whenever Brazil’s coffee yield suffers, such as from frost damage, Colombian coffee enjoys a corresponding increase in international market share. This cycle has played out several times, allowing Colombian coffee to continually ramp up production, fortifying its reputation for both quality and quantity on the global stage.

National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia

It wasn’t a state-led initiative but private organizations that spearheaded the surge in coffee production – a distinctive aspect of Colombian coffee culture. While both Brazil and Costa Rica positioned coffee as an economic linchpin under government directive, in Colombia, it was farm owners and traders who pioneered the formation of the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia (FNC) in 1927.

This body, akin to a farmers’ cooperative, encompasses nearly all coffee stakeholders. It streamlines everything from farming to shipment for producers, purchasing their harvested beans at guaranteed prices. This model assures farmers that they can devote their energies to production without financial worry. The FNC extends its influence from providing technical guidance to farmers, conducting coffee R&D, managing quality, building community hospitals and schools, maintaining roads, to improving farmers’ lives and welfare. Currently, the FNC comprises more than 500,000 households.

Coffee producers submit their harvested beans to the FNC, which in turn handles the export procedures. One-third of the earnings are given in cash, another third is awarded to the producers in bond form. The last third comprises the FNC’s operational fund. The FNC collects a coffee tax from producers and remits it to the national government.

While coffee organizations exist worldwide, none are as large and privately constituted as the FNC. At its inception, coffee comprised 60% of Colombia’s exports. The FNC held such sway over the government and society that it was said the FNC’s president wielded power second only to the country’s President.

The FNC has often executed detailed welfare tasks beyond the government’s scope. A celebrated example occurred in 1985 when the Nevado del Ruiz volcano erupted. The catastrophe engulfed coffee farms and buried villages in mud, claiming over 20,000 lives.

As the Asahi Shimbun’s South American correspondent, I promptly visited the disaster site. As my plane neared the capital, Bogota, a colossal plume of smoke rose above a sea of clouds, with the sulfuric scent pervading the cabin and the fumes stinging my eyes. After a 200km journey on a military relief plane from the landing airport, I hitched a ride on a military helicopter carrying relief supplies to a village 80km away. From there, a 16km truck ride brought me to the mud-enshrouded village of Armero.

Reacting swiftly, the FNC organized a rescue team and transformed a nearby cooperative into a makeshift hospital, packed with beds. The FNC’s nimble response enabled immediate medical action by doctors and nurses from across the country. Emergency medical squads from various countries also played pivotal roles. Among the survivors was a 21-year-old woman, her face and arms appearing as if abraded by a file. After a tormented night struggling in the mud, she finally found respite, thanks to the FNC.

The Rise of a Brand

The FNC also showcased diplomatic prowess that could rival the government’s. Back then, the USA, a significant consumer of coffee, had a habit of procuring beans from producing countries at relatively low costs. As producing nations competed against each other, they had difficulty presenting a united front, leaving the purchasing price largely at the whim of consumer countries. The FNC, however, succeeded in lobbying Brazil to reach an accord on production volume and price.

This type of agreement gradually spread among coffee-producing nations across Central and South America, leading to the 1957 establishment of the Latin American Coffee Cartel. This marked a turning point where producing nations could negotiate with consumer countries on equal footing. This event predated the formation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) by oil-producing nations in 1960 by three years.

At this juncture, the FNC sought to underscore the distinctiveness of Colombian coffee, setting it apart from other Central and South American nations. They conceived the character Juan Valdez – a humble coffee farmer with a mustache, wearing a sombrero hat, a white poncho slung over the shoulder, and leading a mule laden with bags of coffee beans.

This image was televised in the USA. Initially, an actor portrayed Juan, but today, the role is embodied by a real coffee farmer in its third generation. This promotional strategy was a resounding success. Amid recurring coffee crises forcing other producing nations to lower prices, Colombia singularly maintained its high prices. A logo featuring Juan, his mule, and the Andes mountains in the background became synonymous with the assured quality of 100% Colombian coffee.

The branding focus is still prevalent. The gathered coffee beans undergo stringent quality control, with the top 1-3% certified as luxury beans and marketed globally under the “Emerald Mountain” label. Colombia, famous for its high-grade emeralds – the shimmering green gemstone – smartly connected this to its coffee, thus fostering a splendid image of a “drinkable gem.”

Márquez’s Portrayal of the Coffee Culture

Gabriel García Márquez has portrayed his country’s 1950s coffee culture in his works. In his “Chronicles and Reports”, there’s a piece named “How Does Jose Dolores See the Coffee Problem?” It introduces us to a poor coffee farmer, Gutierrez, who tends to 30 coffee trees near the capital. This, however, isn’t enough to feed his mother and two sisters, leading him to also cultivate bananas and peas and additionally pick coffee beans at a larger farm located a few kilometers away.

When a journalist shares with him the impending crash of coffee prices in New York, Gutierrez resolves to store his beans until the prices stabilize. However, he is disheartened by the prospect of no part-time coffee harvesting that year and the mounting impossibility of repaying his farm’s debt.

Meanwhile, the FNC president and the finance minister were in the capital, discussing potential solutions. The talk of the town back then was predominantly about the coffee market prices. The FNC’s representative in New York, who had authored a coffee book in the US, was contemplating promotional strategies to encourage Americans to drink more Colombian coffee.

Amid these developments, the capital’s shoe shiners expressed joy at the falling coffee prices. Despite the rising prices of everything else, they rejoiced at the news of cheaper coffee, exclaiming, “We can drink tinto for five centavos again!” The short story wraps up with these words.

“Tinto” in Spanish means “colored.” In Spain, it’s used to refer to red wine, while in Colombia, it denotes a cup of black coffee. Hence, when ordering coffee at a café, one would say, “Please give me a Tinto.”

Unfortunately, the tinto served in Colombia is far from tasty. The high-quality beans are reserved for export, and the low-quality ones are circulated domestically. This is a common trend across nearly all coffee-exporting countries in Central and South America.

The backbone of Colombian coffee is the poor farmers, much like Gutierrez. Most coffee growers are small-scale farmers like him, or smallholders in a slightly better economic position.

The Culture of Violence

Despite Colombia’s successful endeavor to project a serene image through its delightful coffee, the nation is in reality riddled with violence.

Post-independence from Spain, the country has been witnessing a perpetual tussle between the authority- and control-valuing Conservative Party, and the progressive Liberal Party. This feud escalated into an armed conflict, leading to a civil war from 1899 to 1902, which resulted in the death of 100,000 people. The assassination of a Liberal Party leader in 1948 sparked riots in the capital, thus marking the commencement of a gruesome era of violence that lasted a decade.

Even though the two parties eventually found common ground, the remnants of their discord formed left-wing guerrilla groups. These groups, following ideologies aligned with the Soviet Union, Cuba, and Maoism, were engaged in armed battles. In addition, a week before the infamous 1985 eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, another leftist guerrilla group launched an attack on the Supreme Court in the capital, holding the judges hostage.

To counter this, the government mobilized the military and bombarded the court building with tank and rocket artillery. Despite the guerrillas’ fierce resistance, the standoff resulted in 115 casualties among the hostages, including the Chief Justice, 11 judges, 48 soldiers, and 60 civilians. When I visited the site, I was taken aback by the shell holes visible on the façade of the Supreme Court building. The severity of the government’s response, in spite of the presence of hostages, was shocking.

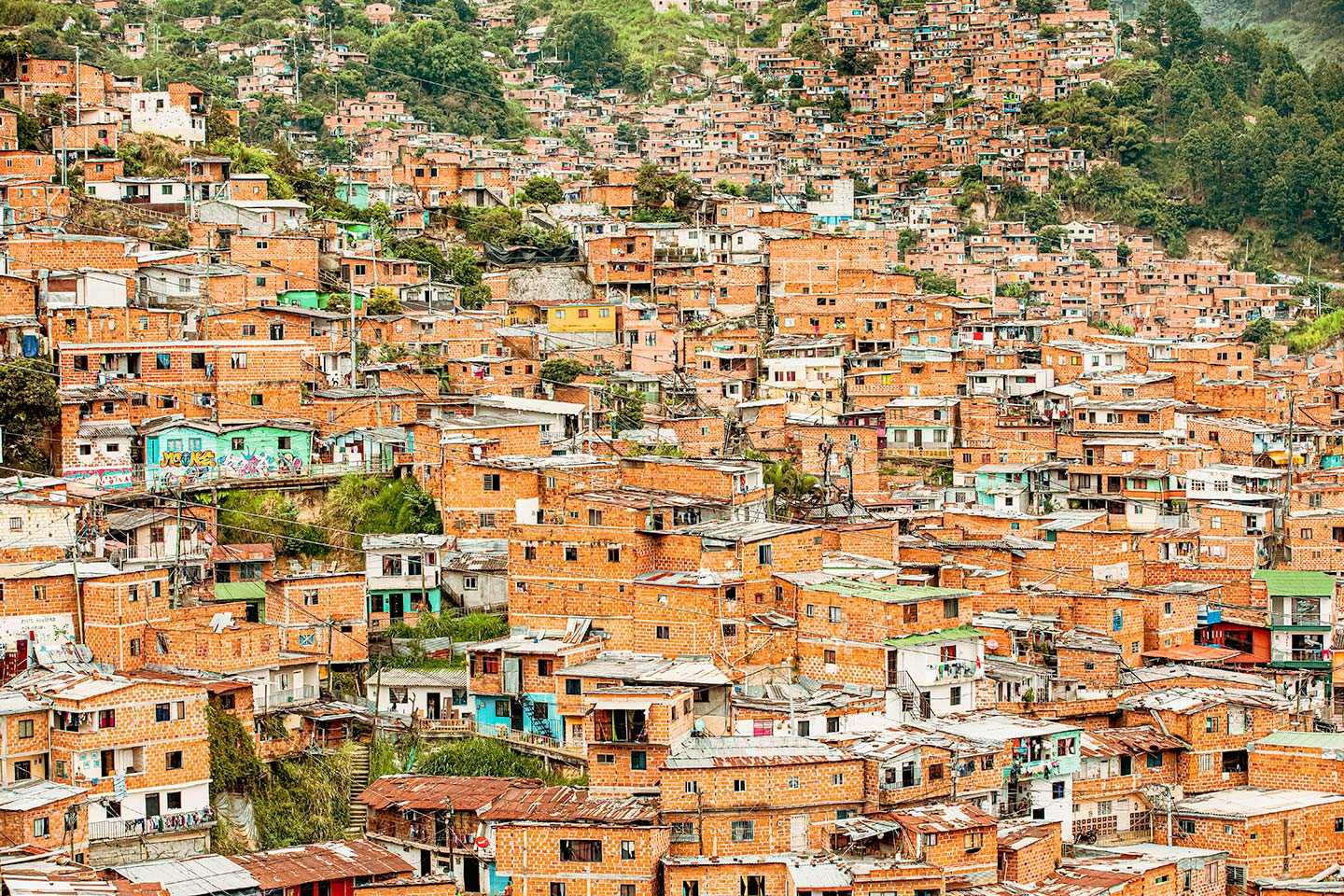

During this period, the world’s largest drug cartel also surfaced. The Medellín Cartel, led by Pablo Escobar and based in the city of Medellín, saw him ascend to the seventh rank among the world’s wealthiest individuals in 1989. He wielded his wealth to manipulate judges and lawmakers, creating territories beyond the government’s reach. Building hospitals, schools, and even zoos, he captured the admiration of the people. Another drug baron created the Cali Cartel in the city of Cali, which eventually triggered the drug war—a deadly battle with the military and police.

Violence is omnipresent. The surreal world that Gabriel García Márquez depicted in his works is a sobering reality in this country. The ‘mild’ coffee birthed from such a hostile environment seems to epitomize the desperate yearning of this nation’s people for a peaceful existence.

*First full-width photo courtesy of Ryan Anderton